A sugar can melt away cholesterol

A sugar that freshens air in rooms may also clean cholesterol out of hardened arteries.

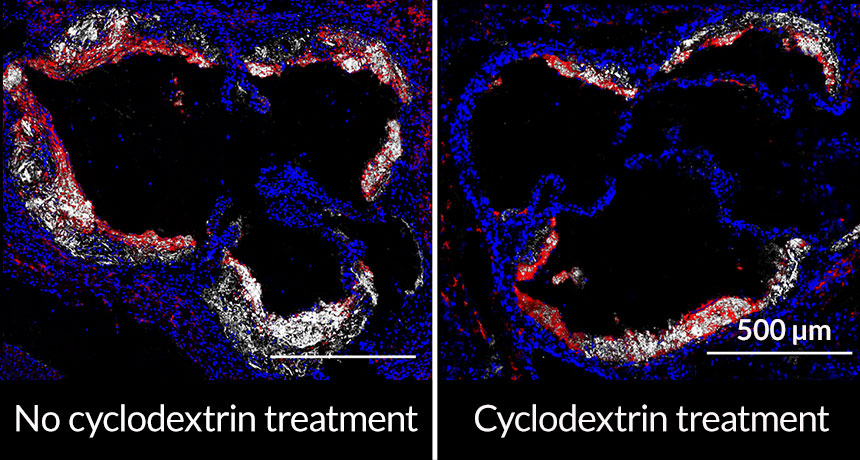

The sugar, cyclodextrin, removed cholesterol that had built up in the arteries of mice fed a high-fat diet, researchers report April 6 in Science Translational Medicine. The sugar enhances a natural cholesterol-removal process and persuades immune cells to soothe inflammation instead of provoking it, say immunologist Eicke Latz and colleagues.

Cyclodextrin, more formally known as 2-hydroxypropyl-beta-cyclodextrin, is the active ingredient in the air freshener Febreze. It is also used in a wide variety of drugs; it helps make hormones, antifungal chemicals, steroids and other compounds soluble. If the new results hold up in human studies, the sugar may also one day be used to liquefy cholesterol that clogs arteries.

Other researchers say the approach is promising, but must be tested in clinical trials. The sweet molecule is generally considered safe, but injecting it may raise the risk of liver damage or hearing loss, says Elena Aikawa, a vascular biologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

Mice taking cyclodextrin in the study did not exhibit side effects from the treatment, but previous work has indicated that the sugar may damage hearing in mice and cats. The molecule shunts cholesterol through the liver, so large cholesterol influxes might cause fat to build up in the liver, impairing its function. “Overall, cyclodextrin seems worth exploring as a therapeutic, although caution should be taken,” Aikawa says.

Cyclodextrin works by flipping a master switch, a gene called LXR, Latz and colleagues found. LXR’s protein turns on other genes involved in processing cholesterol and ushering it out of the body. The sugar also activated the LXR genes in human arteries examined in the lab and turned on inflammation-calming processes, Latz’s team discovered.

Latz, of the University Hospital Bonn in Germany, credits Nevada businesswoman Chris Hempel with the idea to use cyclodextrin to treat atherosclerosis. In people with the condition, cholesterol, calcium, immune cells and other substances form plaques inside arteries, hardening them. Plaques block blood flow and can break away and cause heart attacks and strokes (SN: 2/20/16, p. 32).

Hempel has twin daughters with a rare genetic disease known as Niemann-Pick Type C, in which cholesterol crystals clog organs, especially the brain. In 2009, the girls got special permission from the Food and Drug Administration for their doctor to give them infusions of cyclodextrin to dissolve the cholesterol crystals.

Hempel later read a paper by Latz and colleagues in which the researchers described how cholesterol crystals irritate macrophages and provoke them to cause inflammation and heart disease. Macrophages normally patrol the body and help kill invading bacteria, viruses and other pathogens. The immune cells also gobble up cholesterol and deliver it to the liver where it can be made into bile and escorted out of the body in feces.

Hempel e-mailed Latz and suggested that cyclodextrin might melt the cholesterol crystals in arteries. Latz and his colleagues tested the idea by feeding mice genetically prone to atherosclerosis a high-fat diet and giving the animals regular injections of cyclodextrin under the skin. The sugar kept cholesterol plaques from building up in the rodents’ arteries. The scientists also found that cyclodextrin reduced already established plaques in mice by about 45 percent, even though the animals were still eating a high-fat diet.

Cyclodextrin could be used in combination with other drugs, such as statins, says Eran Elinav, an immunologist at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel. Statins and other drugs inhibit cholesterol production. “Potentially, combining cholesterol lowering with dissolution of preformed cholesterol in plaques could be additive,” Elinav says, “but this option needs to be explored in clinical trials.”

Although cyclodextrin is already approved by the FDA for use in people, it may be years before it’s known whether injecting the sugar will soften people’s hardened arteries. The sugar is not patentable, so no pharmaceutical companies have come forward to sponsor expensive clinical trials needed to get approval for this specific use, Latz says.