Ocean plankton held hostage by pirate viruses

When plankton on the high seas catch a cold, the whole ocean may sneeze. Viruses hijacking these microbes could be an important overlooked factor in tracing how living things trap — or in this case, fail to trap — the climate-warming gas carbon dioxide.

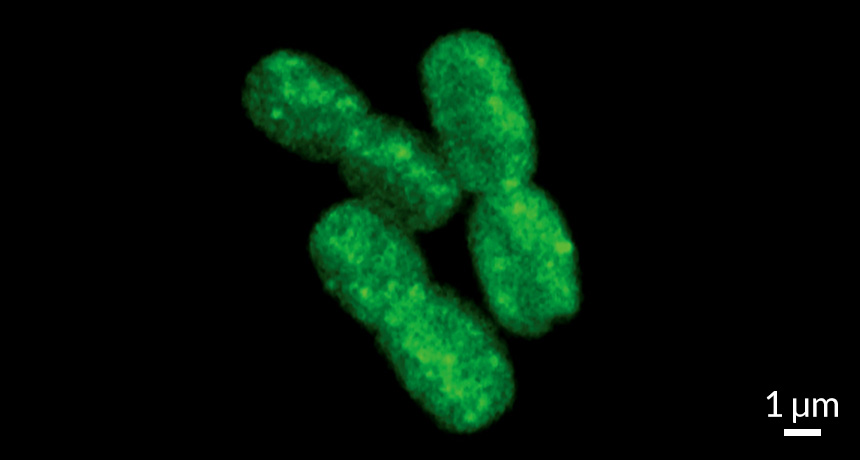

Plants and other organisms that photosynthesize use energy from the sun to capture CO2 for food. The most abundant of these photosynthesizers on the planet are marine cyanobacteria with hardly any name recognition: Synechococcus and Prochlorococcus.

Now, for the first time, a study looks in detail at what happens when some of the abundant viruses found in the sea infect these microbes. Two viruses tested in the lab hijacked cell metabolism, allowing photosynthesis to continue but shunting the captured energy to virus reproduction. The normal use of that energy, capturing CO2, largely shuts down, David Scanlan of the University of Warwick in England and colleagues report online June 9 in Current Biology. As a result, people could be overestimating by 10 percent the amount of CO2 that photosynthesis in the oceans captures.

On any given day, 1 to 60 percent of these plankton may have picked up a viral infection, researchers have estimated. That means that between 0.02 and 5.39 petagrams of carbon — up to 5.39 billion metric tons — may not be captured by marine organisms a year. The high end of that scenario is equivalent to 2.8 times the CO2 routinely captured annually by all the planet’s salt marshes, coral reefs, estuaries, sea grass meadows and seaweeds put together.

Synechococcus and Prochlorococcus plankton “are organisms that you’ve never heard of but you really should have,” says Adam Martiny of the University of California, Irvine. He studies the same kinds of plankton but wasn’t involved in the new virus research, and what he appreciates about it is the intriguing biology of viral manipulation the new work has uncovered.

Until now, Scanlan says, the prevailing view was that while infected plankton were still alive, they were probably carrying on normal photosynthesis. As early as 2003, researchers had clues that the viruses attacking these tiny marine organisms might manipulate photosynthesis in some way, perhaps keeping the process running in an infected cell. These viruses have genes for proteins used in photosynthesis, even though a virus doesn’t even have its own cell much less a way to photosynthesize.

What the viruses are doing, Scanlan and his colleagues have now shown, is subverting their victim’s photosynthesis. Energy capture, the part of photosynthesis directly involved with light, goes on as usual; the cells carry out the routine electron transport for catching energy. But instead of using those sizzling electrons to capture CO2 and turn it into carbohydrates for basic cell metabolism, the viruses shut down this process (called carbon fixation). The light reactions are the ones that researchers normally measure to estimate how much carbon photosynthesis captures in the oceans, but the covert viral shunting means that estimate could be too high.

Scanlan cautions that this is just the beginning of working out the numbers and possible climate effects of virus diseases for these organisms. Whatever the current effects of this takeover turn out to be outside the lab, they may intensify as the climate changes. Synechococcus and Prochlorococcus are “projected to be winners in the new, warmer oceans” and may become even more numerous, Martiny says. And what’s good for them may also increase the abundance of the viral pirates that hijack them.