50 years ago, a millionth of a degree above absolute zero seemed cold

A common pin dropped on a table from a height of one-eighth of an inch generates about 10 ergs of energy, obviously a minuscule amount. That 10 ergs raises temperature, and even that tiny amount is “much too much” to be allowed in the experiment during which Dr. Arthur Spohr of the Naval Research Laboratory reached the lowest temperature yet achieved — within less than a millionth of a degree of absolute zero. — Science News, July 8, 1967.

Update

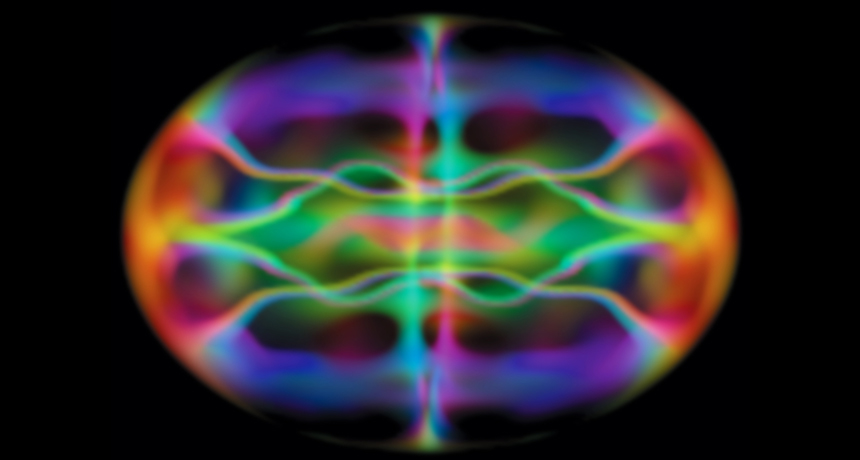

Today, scientists can make clouds of atoms at temperatures as low as 50 trillionths of a degree above absolute zero (SN: 5/16/15, p. 4). Late this year or early next year, NASA will launch its Cold Atom Laboratory to the International Space Station so scientists can study ultracold atoms reaching 100 trillionths of a degree or less. In orbit, gravity doesn’t drag atoms down, so the clouds can stay intact for scientists’ observations for up to 10 seconds — longer than is possible on Earth.