IMEC faces barriers of internal infrastructural issues, Western economic hegemony

At the recent G20 summit, the India-Middle East-Europe Corridor (IMEC) backed by the US, Europe and India under the Partnership for Global Infrastructure Investment was announced. This corridor aims to connect Europe, the Middle East and India with rail and shipping routes.

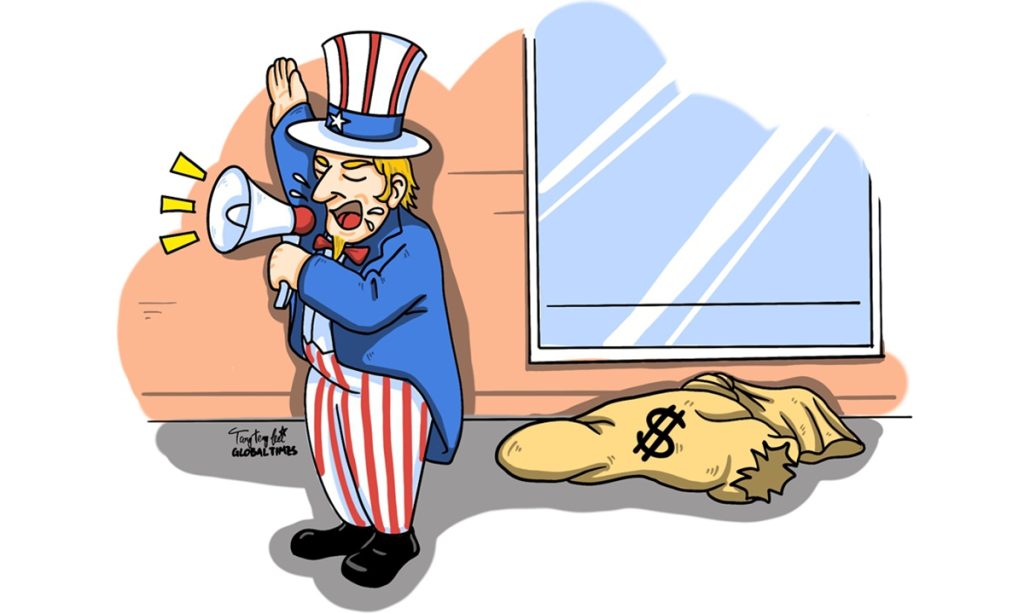

With Biden calling it a "really big deal" and National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan describing the project as "transformative," the project has already been described as one that counters China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which has been signed up to by the majority of the world.

However, the working group tasked with drawing up a fuller plan, over the next sixty days, will have to confront some harsh economic realities relating to funding, material capabilities and the ideological outlook of the main countries involved.

When it comes to funding, let's not forget that the Build Back Better Plan undertaken by the G7 in 2021 to counter the BRI was consigned to the dustbin of history the same year it was announced.

The $1.7 trillion package (less than two years of US defense spending) was considered too costly.

Railway linking India, the Middle East and Europe would be the center piece of the IMEC. When it comes to infrastructure, the US and India do not set good examples for others to follow, yet they expect to compete with China which has first-rate infrastructure. Rather than build something abroad, based on hegemonic competition against China, it would be better for the US and India to demonstrate they can solve the basic democratic infrastructural needs of their citizens first.

Even if internal infrastructural issues and financing can somehow be overcome, the ideological attitude of maintaining economic hegemony that the West holds toward the Global South acts as a barrier to the IMEC. Only with gunship diplomacy could the US force states to buy exclusively from expensive Western companies. Even then, many components will be sourced from China.

At any rate, we are in a multi-polar world now. The Saudi-Iran rapprochement, the enlargement of BRICS, and the good relations in the region toward Russia and China show that the Middle East refuses to take sides and will trade with all. Another Iraqi-style invasion in the region to maintain US-led economic predominance would be foolhardy, as such, the West must be competitive in the market.

Currently, Saudi Arabia is choosing China when it comes to rail construction - though this too is an international effort that pulls in Western companies. The China Railway 18th Bureau Group has already completed the 450km-long Mecca-Medina High-speed Railway and is working on the Medina Tunnel Project along with the Saudi Rua Al Madinah Holding Company, Canada's WSP and US-based Parsons. The linking of Saudi's eastern and western seaboard, while led by China, is also a joint international project. This further highlights the lunacy and impracticality of fencing off the world economy.

One of the major forces driving US hegemonic attempts is its capitalist system which seeks immediate profits. This motivation has led to the decay of US infrastructure and a lack of long-term railway investment; a similar "democratic" system sees India's infrastructure in shambles too. Furthermore, much of the Global South remains in tatters after being harvested by the US military-industrial complex, which seeks quick profits from war and sees development as a threat to its economic hegemony.

In contrast, The BRI is premised on long-term social economic planning. Some projects will not be profitable for decades - many will provide immense social-economic benefits but no profit extraction for private capital. China's socialist system subordinates capital for the democratic good of society and it's because of this that it has the world's largest high-speed rail network, which it can then sell abroad at competitive prices.

In an attempt to conceal China's governing advantages and foresight, the corporate press labels Chinese-involved projects that don't reap immediate profits as "white elephants." Indeed, the debt trap narrative has been constructed to conceal the BRI's long-term planning and misdirect attention from private capital lending, which is far more severe than Chinese loans and the source of much suffering in the Global South.

Certainly, should the IMEC get off the ground without Chinese involvement and sell expensive Western infrastructure, then it will be interesting to observe the Western ideological apparatus scramble to justify how their venture is superior to the BRI, the initiative that the majority of the world has already voluntarily signed up to. There is still an open invitation for Europe, the US and India to join!

The author is an independent international relations analyst who focuses on China's socialist development and global inequality.