The funniest thing I’ve ever said to any botanist was, “What is a species?” Well, it certainly got the most spontaneous laugh. I don’t think Barbara Ertter, who doesn’t remember the long-ago moment, was being mean. Her laugh was more of a “where do I even start” response to an almost impossible question.

At first glance, “species” is a basic vocabulary word schoolchildren can ace on a test by reciting something close to: a group of living things that create fertile offspring when mating with each other but not when mating with outsiders. Ask scientists who devote careers to designating those species, however, and there’s no typical answer. Scientists do not agree.

“You may be stirring up a hornet’s nest,” warns evolutionary zoologist Frank E. Zachos of Austria’s Natural History Museum Vienna when I ask my “what is a species” question. “People sometimes react very emotionally when it comes to species concepts.” He should know, having cataloged 32 of them in his 2016 overview, Species Concepts in Biology.

The widespread schoolroom definition above, known as the biological species concept, is No. 2 in his catalog, which he tactfully arranges in alphabetical order. This single concept has been so pervasive that whenever Science News publishes something about species interbreeding, readers want to know if we have lost our grip on logic. Separate species, by definition, can do no such thing.

As concerned readers question our reports of hybrid species, a vast debate among specialists over how to define and identify species rolls on. The biological species concept has drawbacks, to put it gently, for coping with much of the variety and oddness of life. Alternative concepts have pros and cons, too. As specialists argue over the fine details of species concepts, I’m struck by how often the word “fuzzy” comes up.

Also striking is how at least some of the people who actually appraise species for a living have made peace with the perpetual tumult over defining just what it is they get up in the morning to study. The ambiguities seemed less jarring to me after a September conversation with the Smithsonian’s Kevin de Queiroz, deep in the maze of doors and corridors behind the scenes at the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C. As a systematic biologist, he studies the evolutionary histories of reptiles, and designates species, which explains a door we passed marked “Alcohol Room.” Fire regulations require special handling for jars of animal specimens preserved in alcohol. In the cacophony of species concepts, de Queiroz sees some commonality.

Ertter, affiliated with the University of California, Berkeley and the College of Idaho in Caldwell, embraces the ambiguity. “Why do we expect that nature is nice and neat and clean? Because it’s more convenient for us,” she says. “It’s up to us to figure it out, not to demand that it’s one way or another.”

Problems with the old standard

The biological species concept has an intuitive appeal. Elephants don’t mate with oak trees to produce really big acorns. Horses can mate with donkeys, but the resulting mules are infertile. The most famous form of this species definition may be from evolutionary biologist Ernst Mayr, who wrote in 1942: “Species are groups of actually or potentially interbreeding natural populations, which are reproductively isolated from other such groups.” Famous, yes, but limited.

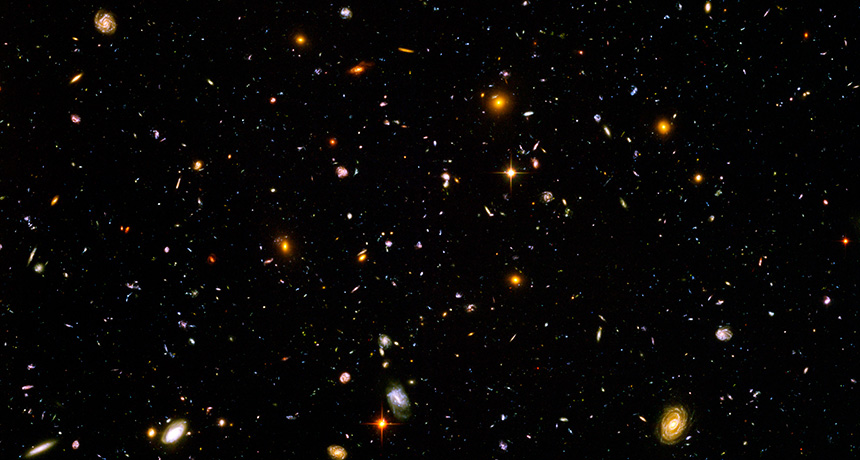

Modern genetics has revealed that much of the diversity of life on Earth is found in single-celled organisms that reproduce asexually by splitting in two — thus flummoxing the definition. Of course the single-celled hordes still form … somethings. There isn’t just one vast smear of microbial life where all shapes, sizes, body features and chemistry can be found in any old mix. There are clusters with shared traits, some of which cause human and agricultural diseases and some of which photosynthesize in the ocean, producing as much as 70 percent of the oxygen that we and other living things breathe. Humans need to understand the history of microbes and have names to talk about these influential organisms.

Rather than deciding that these microbes are just not species, which is one popular view, microbiome researcher Seth Bordenstein suggests “just twisting the biological species concept ever so slightly.” Genes don’t shuffle around via sex, but there’s still kidnapping of genes from other asexuals. This process might count as something like interbreeding, says Bordenstein, of Vanderbilt University in Nashville. With that interpretation, the biological species concept “could apply to microbes.” Sort of.

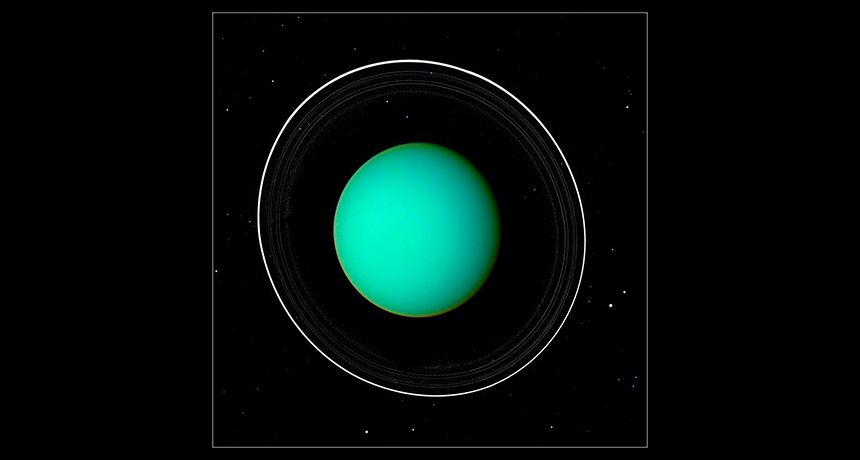

But one-celled microbes aren’t the only asexuals. Even vertebrates have their no-sex scandals. New Mexico whiptail lizards are a species: Aspidoscelis neomexicanus. Yet females lay eggs with no male fertilization; males don’t exist.

And plant reproduction, oy. The blends of sex and no-sex don’t fit into a tidy biological species concept. Consider a new variety of a western North American species that Ertter and botanist Alexa DiNicola of the University of Wisconsin–Madison named this year. Potentilla versicolor var. darrachii belongs to a genus that’s closely related to strawberries. Plants in the genus open little five-petaled flowers and readily form classic seeds that mix genes from pollen and ovule. On occasion, though, the genes in the seed’s embryo are only mom’s. “They basically use seeds as a form of cloning,” Ertter says. The male pollen in these cases merely jump-starts formation of the seed’s food supply.

That’s just one reason Potentilla is “one of the messiest genera you can imagine,” Ertter says. She and DiNicola hauled collectors’ gear on a backpacking trip in Oregon to sample some of the plants. The team found signs that one species was hybridizing readily with another; the species were so different that even a nonbotanist could tell them apart (leaves shaped like a feather versus an open fan). Sharing genes across species is evidently common in this genus and not at all rare among plants.

Such shenanigans have led Ertter to what she calls the “fuzzy species concept.” After looking at all the kinds of evidence she might muster for a plant, from its genes and distribution to the details of petals, leaf hairs and other parts, she sides with the preponderance of data to designate a species.

Concept zoo

There can be a lot of messiness in picking out the limits of species, but that’s OK with philosopher Matt Haber of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. He organized three conferences this year on the complications of determining what’s a species when fire hoses of genetic information spew signs of unexpected gene mixing and tell different stories depending on the genes tracked.

“Just because boundaries are fuzzy,” Haber says, “doesn’t mean they aren’t actually boundaries.” We may not be used to thinking about species distinctions this way, but other familiar distinctions have similar “gradient boundaries,” as he calls them. “Cold and hot weather,” he says. We recognize winter weather as different from summer even though fall and spring have neither a sharp switch point nor a smooth slide. Species, too, could have zones of erratic mixing but still overall be defined as species.

There are a whole lot of species concepts, says Richard Richards, a philosopher of biology at the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa. “We use different rules for different kinds of organisms,” he says. “For vertebrates, the interbreeding rule is useful. Not so for the many kinds of nonsexually reproducing organisms out there.”

What’s called the agamospecies concept applies to asexual organisms and cobbles together genetic or other observable similarities. The ecological species concept emphasizes adaptations to particular environmental zones. The nothospecies concept applies to plants arising when parent species hybridize. And so on. That’s not even counting “the cynical species concept,” which Zachos has heard defining a species as “whatever a taxonomist says it is.”

Land and money

Species definitions can have ramifications, financial and otherwise, for the wider world. Choosing one species concept over another can change how a creature gets classified, which could determine whether conservation laws protect it. The coastal California gnatcatcher’s status as a distinct subspecies makes it eligible for federal protection to keep the bird’s shrub-land as habitat rather than a real estate development. Critics have argued, however, that the bird isn’t distinct enough from its relatives to merit special protection.

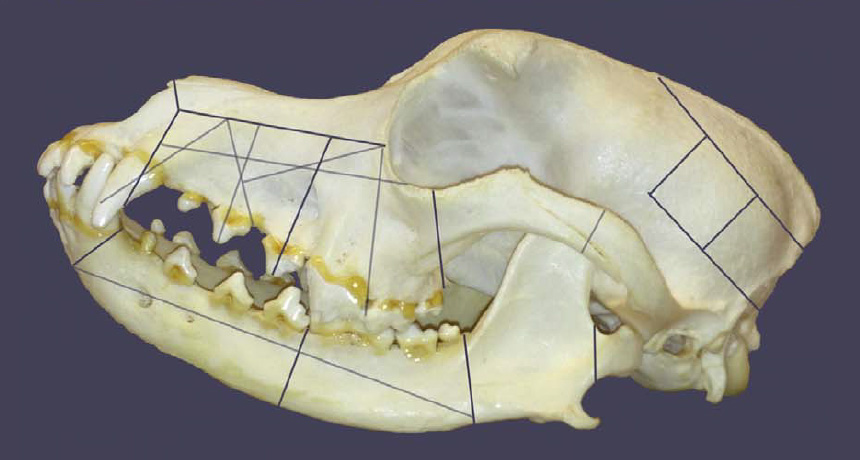

Mammal specialists are switching over to what’s called a phylogenetic concept, Zachos says. The phylogenetic concept allows populations to upgrade to full species status if they share an ancestor and have some unique trait, such as a particular gene. Among the complex consequences of following this concept is possible “taxonomic inflation,” he warns. A 2011 rethink of the ungulate group of sheep, goats, antelope and more ballooned the species count from 143 to 279, for instance. In biology as in economics, “inflation causes devaluation,” Zachos says. “People get bored. If one of the tiger species goes extinct, they say, ‘So what? There are five more.’ ”

As individual taxonomists choose their pet concepts, “ ‘species’ are often created or dismissed arbitrarily,” argued two researchers from Australia in the June 1 Nature. The duo warned of potential “anarchy” and went as far as calling for an international organization to reduce the chaos.

“A long list of silly examples of complications caused by poor taxonomic governance” pushed conservation biologist Stephen Garnett of Charles Darwin University in Darwin to cowrite the piece. Standardizing species concepts across broad groups, mammals and reptiles, for instance, would reduce the chaos, says coauthor Leslie Christidis, a taxonomist at Southern Cross University in Coffs Harbour. The notion of standard-setting in determining species has stirred a bit of agreement and a lot of dissent. “We united the taxonomic community — unfortunately against us,” he says.

The furor illustrates the diversity of ways that people are sorting out what a species is among life’s various organisms. Historian and philosopher of biology John S. Wilkins of the University of Melbourne in Australia was almost kidding when he wrote that there are “n+1 definitions of ‘species’ in a room of n biologists.”

The commons

Thinking about the seemingly intractable ambiguities of the species concepts got a lot easier for me after my visit with de Queiroz. His office was the opposite of the Hollywood biologist’s jumble of dessicated specimens, dangling skeletons and tottering towers of books. The long room was mostly filled with rows of librarian-tidy metal bookcases hiding a desk cave at the far end. When I asked him what a species is, he didn’t laugh. He explained that there’s more agreement than the swarm of species concepts might suggest.

The concepts have in common their references to organisms in a population lineage, or line of descent. As evolutionary time passes, a lineage moves away and its various connected populations grow separate from others of the same ancestry. The concepts share the basic idea that a species is a “separately evolving metapopulation lineage,” he says.

To identify those lineages in practice, however, requires finding evidence of interbreeding or patterns of shared traits. Adding such criteria to the concepts is what creates the crazy diversity. Defining the term species is “not the problem,” he says. “The problem is in identifying a species.”

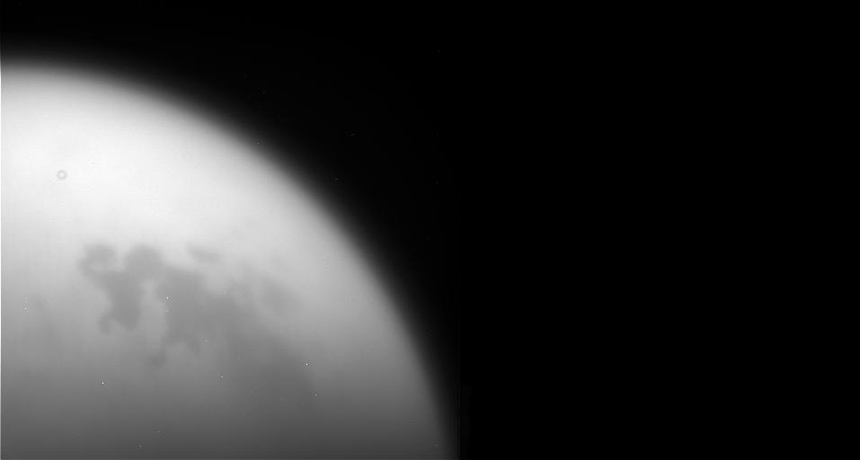

He calls up a map on his computer from a recent paper a former lab member published on fringe-toed lizards. Colored blobs float over dark lines of a map of the western United States. Three blobs are clearly designated species based on multiple lines of evidence. Three lizard patches, however, are perplexing. Various ways of testing these lizard populations lead to contradictory results.

No matter how badly we want the process of applying a species definition to be clear-cut for all creatures in all cases, “it just isn’t,” de Queiroz says. And that’s exactly what evolutionary biology predicts. Evolution is an ongoing process, with lineages splitting or rejoining at their own pace. Exploring a living, ever-evolving world of life means finding and accepting fuzziness.