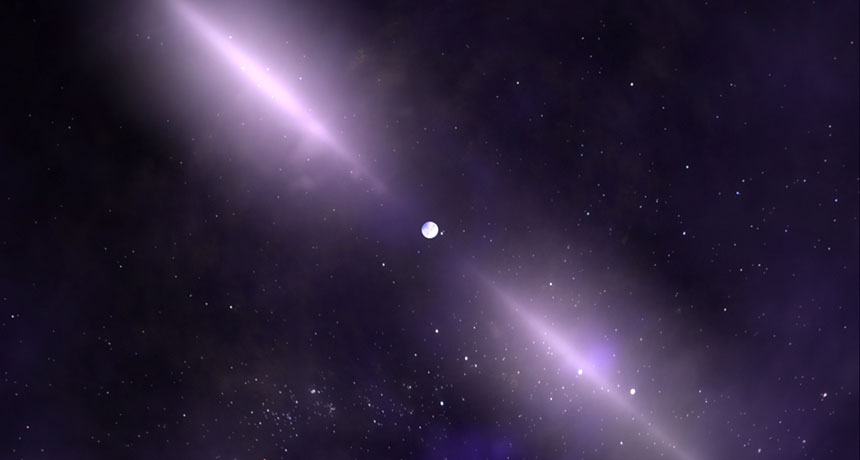

Here’s when the universe’s first stars may have been born

For the first time, scientists may have detected hints of the universe’s primordial sunrise, when the first twinkles of starlight appeared in the cosmos.

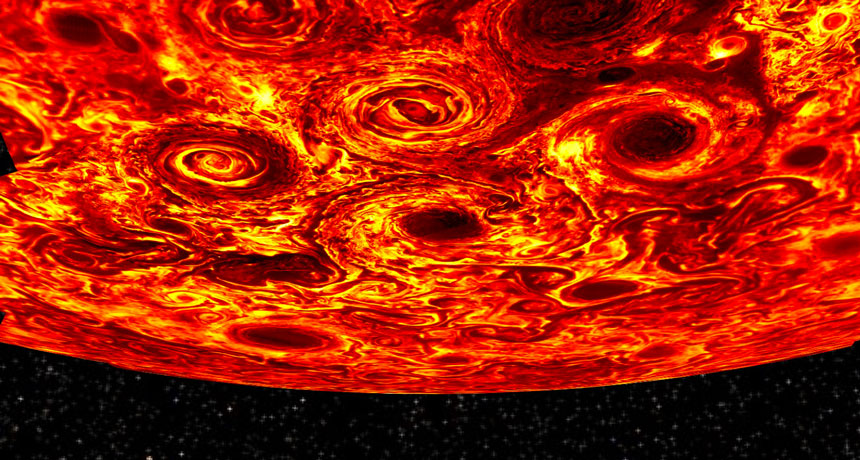

Stars began illuminating the heavens by about 180 million years after the universe was born, researchers report in the March 1 Nature. This “cosmic dawn” left its mark on the hydrogen gas that surrounded the stars (SN: 6/8/02, p. 362). Now, a radio antenna has reportedly picked up that resulting signature.

“It’s a tremendously exciting result. It’s the first time we’ve possibly had a glimpse of this era of cosmic history,” says observational cosmologist H. Cynthia Chiang of the University of KwaZulu-Natal in Durban, South Africa, who was not involved in the research.

The oldest galaxies seen directly with telescopes sent their starlight from significantly later: several hundreds of millions of years after the Big Bang, which occurred about 13.8 billion years ago. The new observation used a technique, over a decade in the making, that relies on probing the hydrogen gas that filled the early universe. That approach holds promise for the future of cosmology: More advanced measurements may eventually reveal details of the early universe throughout its most difficult-to-observe eras.

But experts say the result needs additional confirmation, in particular because the signature doesn’t fully agree with theoretical predictions. The signal — a dip in the intensity of radio waves across certain frequencies — was more than twice as strong as expected.

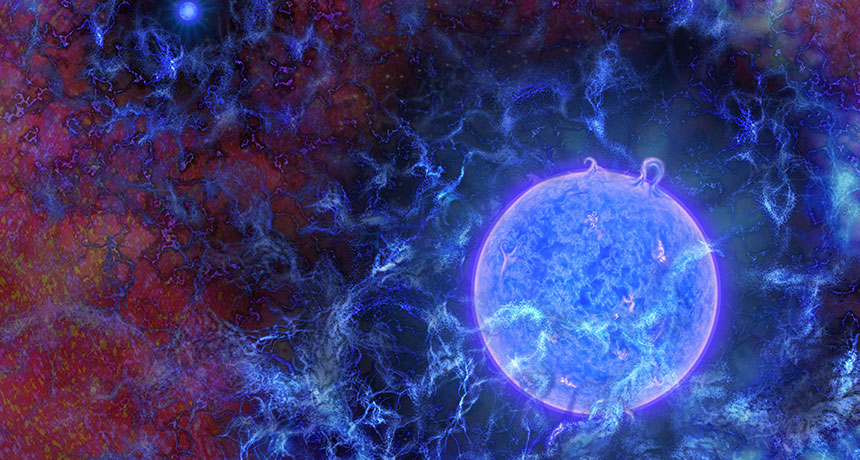

The unexpectedly large observed signal suggests that the hydrogen gas was colder than predicted. If confirmed, this observation might hint at a new phenomenon taking place in the early universe. One possibility, suggested in a companion paper in Nature by theoretical astrophysicist Rennan Barkana of Tel Aviv University, is that the hydrogen was cooled due to new types of interactions between the hydrogen and particles of dark matter, a mysterious substance that makes up most of the matter in the universe.

If the interpretation is correct, “it’s quite possible that this is worth two Nobel Prizes,” says theoretical astrophysicist Avi Loeb of Harvard University, who was not involved with the work. One prize could be given for detecting the signature of the cosmic dawn, and another for the dark matter implications. But Loeb expresses reservations about the result: “What makes me a bit nervous is the fact that the [signal] that they see doesn’t look like what we expected.”

To increase scientists’ confidence, the result must be verified by other experiments and additional tests, says theoretical cosmologist Matias Zaldarriaga of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, N.J. Several other efforts to detect the signal are already under way.

Experimental cosmologist Judd Bowman of Arizona State University in Tempe and colleagues teased out their evidence for the first stars from the impact the light had on hydrogen gas. “We don’t see the starlight itself. We see indirectly the effect that the starlight would have had” on the cosmic environment, says Bowman, a collaborator on the Experiment to Detect the Global Epoch of Reionization Signature, EDGES, which detected the stars’ traces.

Collapsing out of dense pockets of hydrogen gas early in the universe’s history, the first stars flickered on, emitting ultraviolet light that interacted with the surrounding hydrogen. The starlight altered the proportion of hydrogen atoms found in different energy levels. That change caused the gas to absorb light of a particular wavelength, about 21 centimeters, from the cosmic microwave background — the glow left over from around 380,000 years after the Big Bang (SN: 3/21/15, p. 7). A distinctive dip in the intensity of the light at that wavelength appeared as a result.

Over time, that light’s wavelength was stretched to several meters by the expansion of the universe, before being detected on Earth as radio waves. Observing the amount of stretching that had taken place in the light allowed the researchers to pinpoint how long after the Big Bang the light was absorbed, revealing when the first stars turned on.

Still, detecting the faint dip was a challenge: Other cosmic sources, such as the Milky Way, emit radio waves at much higher levels, which must be accounted for. And to avoid interference from sources on Earth — like FM radio stations — Bowman and colleagues set up their table-sized antenna far from civilization, at the Murchison Radio-astronomy Observatory in the western Australian outback.

Scientists hope to use similar techniques with future, more advanced instruments to map out where in the sky stars first started forming, and to reveal other periods early in the universe’s history. “This is really the first step in what’s going to become a new and exciting field,” Bowman says.